Words and Light

Have you ever wondered what it would be like to be blind? If so, whatever you’ve imagined is probably wrong. According to Jacques Lusseyran, who lost his sight in an accident when he was eight years old, the world doesn’t go dark. On the contrary, it gets flooded with light and color.

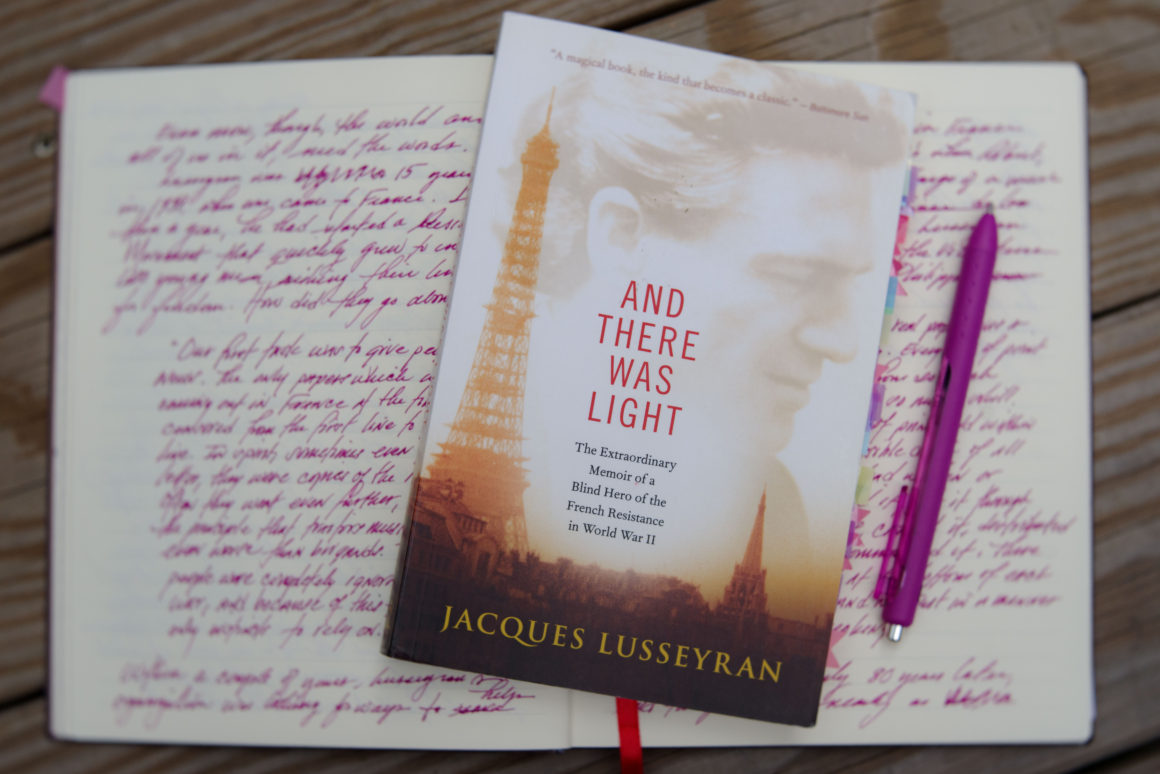

In And There Was Light, the story of his first 20 years, Lusseyran writes, “It was exactly as if I needed light to live—needed it as much as air.”

Reading that sentence again (for the fifth, sixth, seventh time?), I realize that I need words to live: my own and others’.

In placing books back on the shelves after Dennis painted the family room recently, I took notice of one I read five or six years ago: The Power of Silence by Cardinal Robert Sarah, and since then, I’ve called up the phrase, “the power of silence” any number of times as a sort of reminder to sit tight, keep quiet, see what happens.

It turns out that it’s no good. I need the words for reasons I’m just beginning to understand.

It turns out that I’m not the only one. The world—all of us in it—needs the words.

Lusseyran was 15 years old in 1939, when war came to France. In less than a year, he had started a Resistance organization, the Volunteers of Liberty, that quickly grew to include 600 young men risking their lives for freedom. How did they go about it?

Our first task was to give people the news. The only papers which were coming out in France at the time were censored from the first line to the last line. In spirit, sometimes even to the letter, they were copies of the Nazi press. Often they went even further, following the principle that traitors must behave even worse than brigands. The French people were completely ignorant of the war, and because of this they had only instincts to rely on.

Within a couple of years, Lusseyran’s organization was looking for ways to help Allied pilots shot down in France get to safety in Spain. That’s when Robert, and through him, Philippe, came into Lusseyran’s life. Philippe was running an organization called Defense de la France, which published an underground newspaper with a circulation of ten thousand a month. Soon enough, Lusseyran and his compatriots voted to merge with Defense, thereby consolidating and strengthening their efforts:

In 1943 a real paper was a precious thing. Every line of print was drawn from so much courage and so much skill. Every line of print held within it the possible death of all those who had written or composed it, put it through the press, carried it, distributed it and commented on it. There was blood at the bottom of each page, and not just in a manner of speaking.

So, here we are, nearly 80 years later, and things aren’t nearly as deadly—or are they? In the 20th century, the Nazis got away with snuffing out thousands of lives on a daily basis because they managed to keep their atrocities a secret or convince the masses that those exposing these crimes were not to be trusted. What has really changed since then, beside the methods of warfare and the details of the circumstances?