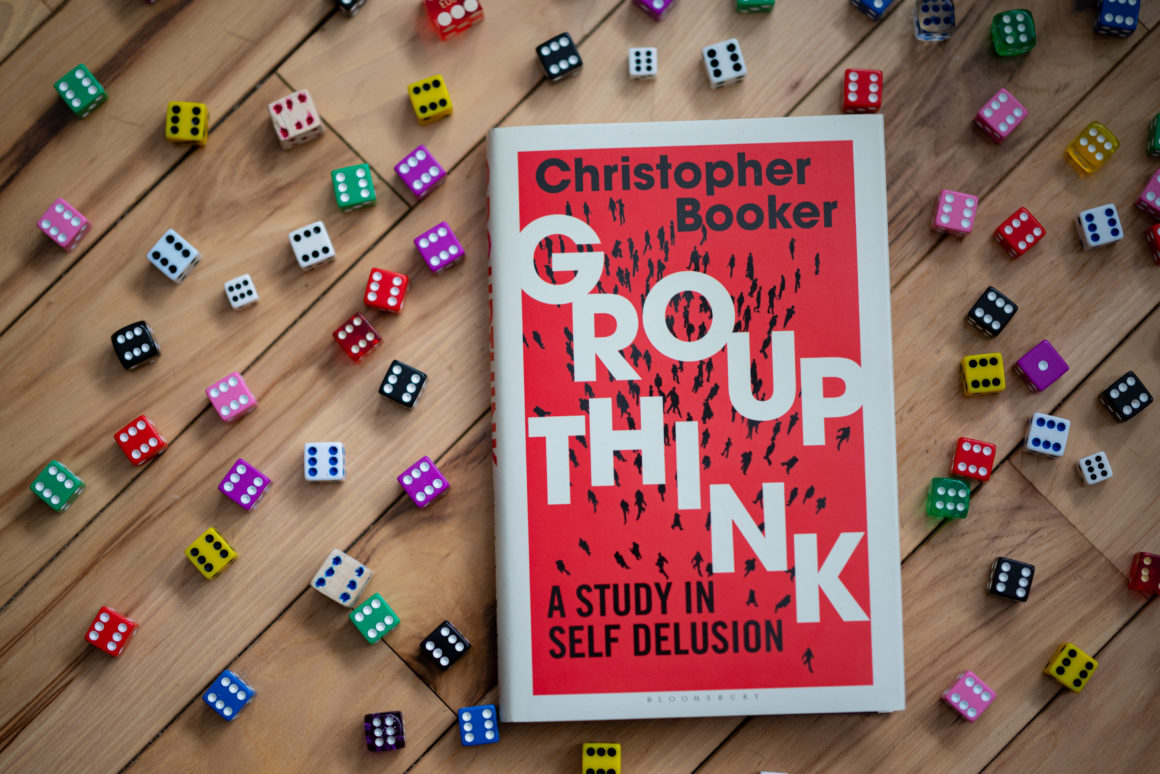

Groupthink

Groupthink: A Study in Self Delusion turned out to be rather a different book that what I thought I was in for. I sometimes buy books impetuously, skimming descriptions as quickly as possible, glancing at a review or two, and such was the case with this. The title is what attracted me to the book. I knew nothing about author Christopher Booker, who sadly died of cancer at age 81 in July of 2019, before he could finish the book, so the closing was taken up by his friend and colleague Richard North and his son, Nicholas. It turns out that Booker was a Brit with a number of books to his name (one on stories that I will be looking into). He was also founder and editor of satirical news magazine Private Eye, and a longstanding columnist for The Sunday Telegraph.

It turns out that Booker was first and foremost, then, an observer and commentator—I suppose, as all good writers should be. He begins this book with an introduction to the rules of groupthink, a term, he explains, that was not coined, but defined, by Irving Janis, a professor of psychology at Yale, in his 1972 book, Victims of Groupthink. So, how does Janis define it? Here is the excerpt from Janis’s book with which Booker begins his introduction:

I use the term “groupthink” as a quick and easy way to refer to a mode of thinking that people engage in when they are deeply involved in a cohesive in-group, when the members’ strivings for unanimity over-ride their motivation to realistically appraise alternative courses of action.

Groupthink is a term of the same order as the words in the Newspeak vocabulary George Orwell presents in his dismaying 1984—a vocabulary with terms such as “doublethink” and “crimethink”. By putting groupthink with those Orwellian words, I realise that groupthink takes on an Orwellian connotation. The invidiousness is intentional: groupthink refers to a deterioration of mental efficiency, reality testing and moral judgment.

According to Booker, groupthink is defined by three rules:

1. That a group of people come to share a common view, opinion or belief that in some way is not based on objective reality. …

2. That, precisely because their shared view is essentially subjective, they need to go out of their way to insist it is so self-evidently right that a “consensus” of all right-minded people must agree with it. Their belief has made them an “in-group,” which accepts that any evidence which contradicts it, and the views of anyone who does not agree with it, can be disregarded.

3. … To reinforce their “in-group” conviction that they are right, they need to treat the views of anyone who questions it as wholly unacceptable. They are incapable of engaging in any serious dialogue or debate with those who disagree with them. Those outside the bubble must be marginalized and ignored, although, if necessary, their views must be mercilessly caricatured to make them seem ridiculous. If this is not enough, they must be attacked in the most violently contemptuous terms, usually with the aid of some scornfully dismissive label, and somehow morally discredited. The thing which most characterizes any form of groupthink is that dissent cannot be tolerated.

One would need to be completely disingenuous or living under a rock not to see how society has been in the grip of groupthink for decades, and things are only getting worse. Something has to break, and soon.

Booker spends a large portion of his book on the subject of political correctness, as well he should, as such an overriding and thoroughly cultivated tactic of propaganda—which involves new concepts like “the weaponizing of words,” obsessions about offending someone for something, reducing every issue to either/or, labeling, and censoring—is crucial to moving into an environment that criminalizes free speech and free thought.

Once Booker has established and fleshed out the nature of political correctness, he gets down to the business of how groupthink has taken form in the arenas of 1960s cultural shifts, establishment of the European Union, global warming, and Darwinism. North, in the concluding chapter he has contributed, fills the reader in on Booker’s thoughts and writings on Brexit, a subject Booker had hoped to include. All of this turns out to be what makes the book something other than expected for me. If I had looked more closely at what I was purchasing, I might never have bothered with the book. That’s not to say that these subjects hold no interest for me; it’s that I was already aware of them and the lies used to sell most of them, at least at some level. So, in some instances, I learned a thing or two of interest, but in others, Booker was sharing details that weren’t especially meaningful to me. That being said, I did find it interesting to learn of the provenance of “groupthink” and see it applied to issues that have (unfortunately) gripped the world in the recent past. I do not think, however, that Booker was working with the entire story. His naïveté about the social engineering involved in these issues and who is responsible was not surprising but slightly disappointing. What’s more, I think he would have had a field day with the Covid plandemic and the groupthink that has been used to advantage by its creators to divide the people of the world, sell the “cure” for what they created, usher in draconian measures that strip people of their freedom and their dignity, and mainstream the idea that humans are little more than disease vectors just waiting to unleash immunological hell on anyone who dares to get within six feet.