An Unfinished Film and Missing Pieces

Oh, what a world. These are interesting times, and I spend much of my day watching the movie that is playing on the screen. How will it end? I think I know, but we have not gotten to the climax, so I stay on the edge of my seat. Every now and again, I share what I’ve seen, what I’ve heard, what I know, but most of my fellow viewers are lost, and I’m generally just wasting my breath. They never watched the prequels, don’t understand who the characters are, and get the storylines all wrong. They think they walked into the theater showing the latest Avengers extravaganza, but they bought a ticket for War and Peace. I work hard to keep this in mind, because I forget, I get frustrated, and frustration makes it hard to hold onto peace of heart.

My viewing experience is helped greatly by the books I have read/am reading. It may take me a year or more to get to the end of Maps of Meaning by Jordan B. Peterson, but my slow, steady, careful study of it has already paid off, and I have not even reached the halfway point. Perhaps most importantly, I am coming to understand just how intricately ancient civilizations and their cultural/religious practices are entwined with all of our institutions and conventions. Most of us are blind to this situation, but that doesn’t mean it does not exist.

What we accept as true and how we act are no longer commensurate. We carry on as if our experience has meaning—as if our activities have transcendent value—but we are unable to justify this belief intellectually. We have become trapped by our own capacity for abstraction: it provides us with accurate descriptive information but also undermines our belief in the utility and meaning of existence. This problem has frequently been regarded as tragic (it seems to me, at least, ridiculous)—and has been thoroughly explored in existential philosophy and literature.

—Jordan Peterson

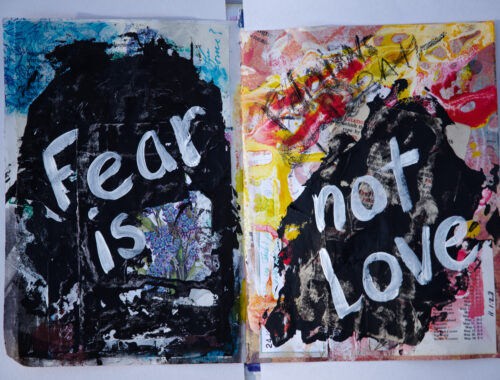

We—this great, scientific/technological/rational society—are no longer able to think logically. It might sound paradoxical, but when you erase great swaths of what humans have always understood and felt because “that’s just superstition or religion or primitive nonsense,” you end up calling finished a jigsaw puzzle with great gobs of missing sections. In fact, you haven’t even gotten all of the border pieces connected.

As Luigi Giussani carefully made clear in The Religious Sense, reason is not the opposite of faith. Reason is simply the human capacity to take in everything encountered and think about it. When, however, you define reason as whatever is “scientifically provable” (whatever that means), you throw away 90 percent of those puzzle pieces.